Welcome back,

China‘s Impact on

Investment PORTFOLIO Decisions

My dear Friends,

since China´s reopening after strict Covid-19 lockdowns in January 2023, politicians across the Globe busied themselves with travelling to China. Mostly having a sizable group of business people with them.

Apart from the usual and not-so-usual political talks, there was a lot of noise regarding economic worries, decoupling and trade relations.

Investors coming from the Western hemisphere, however, seem more interested in what happens on Wall Street and in the US economy to get information for investment portfolio impact.

Did you ever ask yourself the question if some of the recent stock market fluctuations may directly result from what’s happening in China? Could it be that future investment portfolio decisions should not be made without keeping a close watch on China´s economic position in the global economy?

It is high time to take a closer look at how China could influence portfolio decision-making.

China´s rapid rise

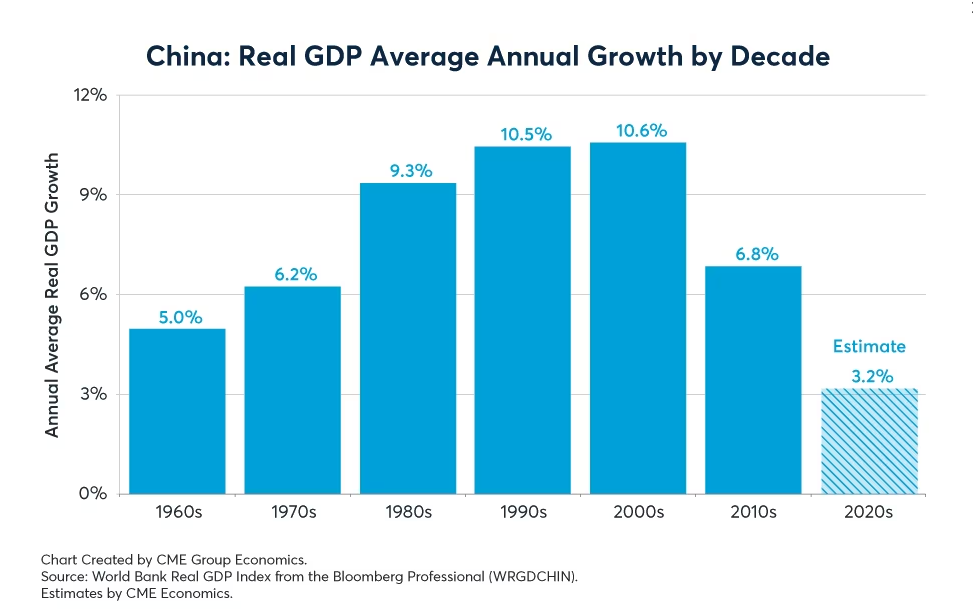

Since opening up to foreign trade and investment and implementing free-market reforms in 1979, China has been among the world’s fastest-growing economies. China´s real annual gross domestic product (GDP) grew by an average of 9.5% up to 2018. The World Bank described China’s growth as “the fastest sustained expansion by a major economy in history.”

Economy prior to reforms

Forty years ago, before China started major economic reforms, it had maintained policies that kept the economy very poor. China was, in fact, one of the poorest countries in the world. The wealth of people in China has grown faster than anywhere else in the world, giving its citizens a median personal wealth of $26,752, compared to a European’s $26,690.

Prior to 1979, China´s leader Chairman Mao Zedong maintained a communist-style centrally planned, or command, economy. The country’s economic output was directed and controlled by the state. The government set production goals, controlled prices, and allocated resources throughout most of the economy. Throughout the 1950s, all of China’s individual household farms were collectivized into large communes.

Nearly three-fourths of industrial production was produced by centrally controlled, state-owned enterprises. Private enterprises and foreign-invested firms were generally barred. A central goal of the Chinese government was to make China’s economy relatively self-sufficient.

The economy suffered significant economic downturns during Mao Zedongs leadership. The Great Leap Forward, from 1958 to 1962, led to massive famine. Reportedly up to 45 million people died. Further, the Cultural Revolution from 1966 to 1976 did not only cause widespread political chaos but greatly disrupted the economy. Between 1958 to 1962, Chinese living standards fell by 20.3%, and from 1966 to 1968, by 9.6%.

Economic growth and reforms

Beginning in 1979, China launched several economic reforms. The central government initiated price and ownership incentives for farmers. This enabled them to sell a portion of their crops on the free market. In addition, the government established four special economic zones along the coast to attract foreign investment and boost exports. At the same time, China started to import high-technology products. Thus modernising its industries.

Additional reforms, which followed in stages, sought to decentralize economic policymaking in several sectors, especially trade. Economic control of various enterprises was given to provincial and local governments, which were generally allowed to operate and compete on free market principles. In addition, citizens were encouraged to start their own businesses.

Unstoppable rise

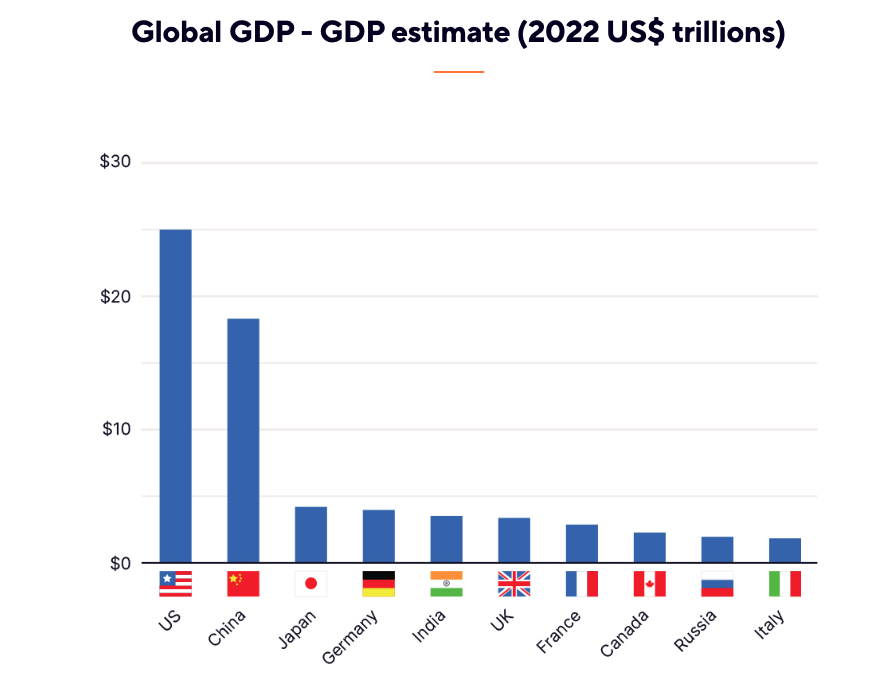

In 2020, the World Bank valued the Chinese economy at $14.7 trillion. Today China is the second largest contributor to global gross domestic product (GDP) and, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), will represent 18% of global GDP in 2022. In 2000, China´s GDP came sixth behind the US, Japan, Germany, the United Kingdom and France.

Yet only 40 years ago, the Chinese economy was in its infancy, valued at a mere $191 billion in 1980. Within 20 years, the size of the Chinese economy had crossed the trillion-dollar mark for the first time in 1998. Many analysts saw this as the awakening of a sleeping giant. China´s vast resource of people was considered a catalyst for future growth in China. For one, the vast population would provide cheap labour. Second, with a fast-growing number of new consumers, the world had a new market it could sell its good.

On average, China doubled its GDP every eight years and helped raise an estimated 800 million people out of poverty.

Today China is the world’s second-largest economy, manufacturer, merchandise trader, and holder of foreign exchange reserves.

China´s move from being an underdeveloped economy to holding the status of a mature economy was certainly a fast-paced one.

Holding sway

China rose into the upper echelons of the world economic order. Its status as an economic powerhouse is indisputable. Today the country‘s appetite for commodities, from grains to energy and from metals to consumer goods and technology, determines how the global economy performs.

Today the country is a key bilateral trading partner and an important investor in resource-rich nations.

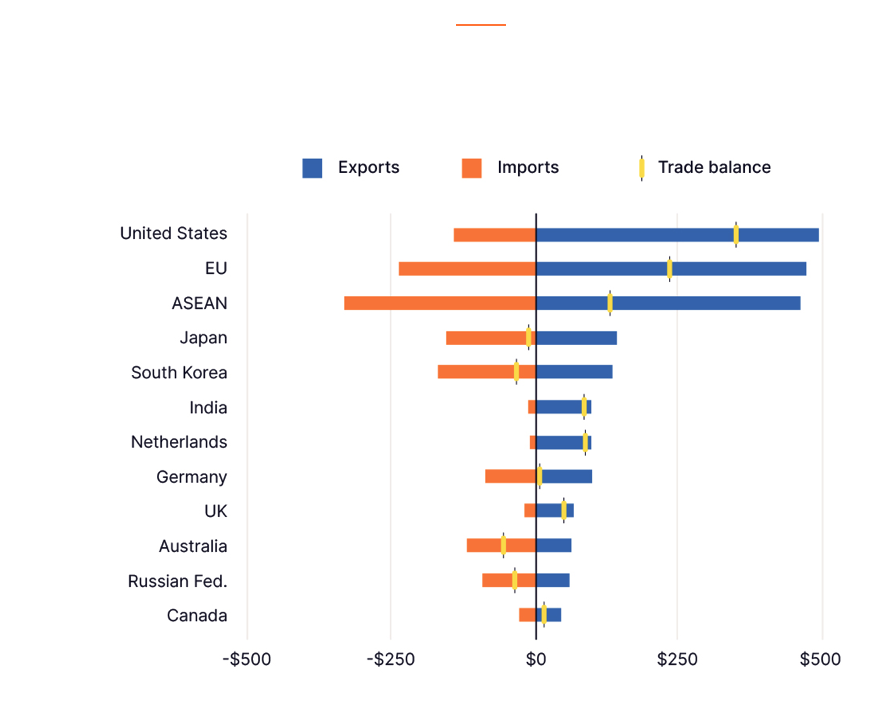

Trade relationships with China have gained importance over the years. Yet, it is a two-way street. China still depends on the rest of the world for its growth. This has been pivotal to China’s emergence as the world’s second-largest economy behind the United States.

Together, the U.S. and China account for 43% of the global economy, valued at around $85 trillion in 2020, reflecting their influence with every twist and turn of their own respective pace of growth.

Factory of the world

The global dependence on China as a “factory to the world” became evident during the height of the pandemic when its lockdowns snarled supply chains. The subsequent rise in inflation as a confined world rapidly shifted its demand from services to manufactured goods produced primarily in China.

Exports have been the centrepiece of the Chinese economy, and their growth over the years has been significant.

In 1990, China exported a mere $60 billion worth of goods and services. Exports began to take off in earnest in 2002, from $256 billion to $1.61 trillion in 2008. Exports During the recession that year exports dwindled. The recovery began in 2009 to top $2 trillion in 2011 and $2.7 trillion in 2014.

When most think about China’s exports, electronics such as televisions and cell phones, as well as textiles, furniture, toys and athletic wear, immediately come to mind. Brands like Nike, Addidas, Zara and even Haute Couture Brands would be a lot less successful without China.

Covid lockdowns in China resulted in a sharp and intense fall in the export of Chinese goods and a collapse of the value chains. This took its toll on an array of manufacturers across the globe, from solar panel manufacturers to the pharmaceutical industry. Companies like Apple, Boing, Starbucks and Germany’s car industry took severe hits that resulted in less output and consequently fewer sales and less profit.

An insatiable hunger for goods

For example, China is the most important external market for the U.S. and Brazilian agricultural sectors. It imports vast amounts of soybeans and corn for its livestock industries.

Until recently, China was not only the second-biggest market for European car manufacturers and heavy machinery; also, 20% of its chemical and 35% of other industrial output went to China. Thus, making China the most important trading partner for the European Union.

However, it does not stop there; China is the most important country for the luxury goods industry, from fashion to cosmetics. Without the Chinese market, this sector would have hardly had any growth in recent years.

Due to the strict covid lockdowns, for example, Luxury spending by Chinese nationals had dipped from 33% of the global personal luxury goods market in 2019 to as little as 17%. This had significant consequences on the value/share price of these companies.

China´s biggest weakness, however, is its dependency on foreign imports when it comes to semiconductors. China is currently the world’s largest semiconductor market in terms of consumption. In 2020, China represented 53.7% of worldwide chip sales or $239.45 billion out of $446.1 billion.

However, raw materials used in manufacturing, such as iron and copper, account for the bulk of imports into China. Countries in Africa, Latin America and Asia provide the minerals and other resources the Chinese industries require to keep them humming along. For some countries, export to China accounts for 98% of their total export volume.

There is another dependency on imports. Crude oil and gas fuel the country’s transportation needs and economic growth. China imports both in huge quantities and thus making it an important trading partner for oil and gas-producing countries.

The headwinds

Most recently, China’s economy has slowed sharply in late 2021 and early 2022 to below 5% growth rates. Yet China wasn´t alone in experiencing a slowdown. The recent pandemic left a dent in most economies no matter how much money governments threw at their people and the economy.

However, China‘s 2023 growth numbers of 4,5% in Q1 give hope. The world’s second-biggest economy might have turned a corner. But the recovery was uneven and bolstered by a low base effect.

However, optimistic as ever, global stock markets concluded that China’s above-expected growth date could drive the global economy. The result: a cautious upward trend.

There are, however, some elephants in the room, and many questions about the country’s management of the economy and private enterprise remain. Market players seemingly forgot that it was the millions of deprived consumers who drove the growth numbers after shops had reopened.

A slow-motion financial crisis

The property sector, which has accounted for about a quarter of the gross domestic product over the past decade, is still a drag. After the 2022 crisis, construction of new homes, offices and stores fell 5.8 per cent year-on-year.

China‘s vast real estate sector is suffering from running up too much debt. Apartments were bought before they were built, and most paying mortgages on properties still under construction. When construction slowed or stopped, the buyers were left behind with mere construction sites and a substantial loss of money.

The property market´s downturn is a major drag on China‘s economy. A government campaign to rein in reckless borrowing and curb speculative trading worsened things. Property prices fell further, as have sales of new homes. This could ultimately lead to a major banking crisis in China.

Because Beijing allowed rapid credit growth to go unchecked, the government lost considerable credibility. Within China and abroad. Economy growth was largely due to a self-reinforcing cycle of rising property prices, more construction activity, rising land prices and growing land revenues for local governments, and credit growth. Any long-term economic consequences for China or the global economy at large are unforeseeable.

Party Policies

When Chinese leader Xi Jinping came to power in 2012, he unveiled a sweeping vision for the “great rejuvenation” of the country. He promised to make China powerful and prosperous.

However, economic growth was never imperative to Chairman Xi. Consequently, he reasserted government control of many aspects of people’s lives, with widespread economic impacts.

With economic growth secondary to political control, China’s consumers and businesses suffer, at least relative to where they might have been. Because of China‘s importance in the global economy, the very same might have to pay the price as well.

“Chinese authorities are prioritizing social welfare and wealth redistribution over capital markets in areas that are deemed social necessities and public goods,”

Goldman Sachs Analyst

The recent aggressive bid for control, however, isn’t about creating chaos. But about making it quite clear to its corporate champions that tapping capitalist markets is fine. Provided it is on the ruling Chinese Communist Party’s terms.

For many powerful Chinese companies, the recent crackdown on private enterprise wiped out more than $1.2 trillion in market value. Global fear about the future of innovation in the world‘s second-largest economy grew.

Shrinking population

China’s vast labour and consumer force has been instrumental in the country’s growth. Now, however, the overall labour force is shrinking, with more people leaving the workforce than entering it.

China´s shrinking population, however, is not only the result of an ageing population but is largely due to the one-child policy that was only abandoned in 2016.

Irrespective of Bejing now allowing couples to have three children per family, many couples are reluctant actually to have more than one child. As many Chinese in their 20s and 30s were born into one-child families themselves, they are largely overwhelmed by the idea of having more than one child.

The one-child policy also contributes to there being more men than women. Resulting in more men facing fewer women. Additionally, increasing numbers of women are also less willing to reproduce. A phenomenon China shares with the rest of the developed world.

Further, the high costs of child care and housing do not help to raise a child. As a result, many young people continue to stick with the one-child family concept.

Overall demographic results show a rapid increase of Chinese in the over-65 category. A fact, however, not much different from other developed countries around the globe.

Alas, importers and the country‘s service industry will have to face lesser or different demands due to a shrinking and ageing population. This will have ripple effects within countries and industries whose economic stability depends on ever-hungry Chinese consumers.

Decoupling-Diversification

Businesses that do a large volume of transactions with China, either as buyers or sellers, should consider how the shift to political control of the economy will impact them. This is independent of the size or growth of the Chinese economy overall.

Already companies around the globe that rely on Chinese suppliers are worrying about further supply chain snarls as experienced during China´s Zero Covid policy.

The potential for war over Taiwan has increased as Xi clarified that politics and control are more important than the economy. Many businesses that have been either buying Chinese products or selling their products in China cannot make a sudden change in all of their suppliers or shift to other markets. However, gradual adjustments can already be noticed. However, nobody truly knows what the long-term economic consequences of a move away from China may be.

Still in its infancy

As for the Chinese stock market, the best analogy might be that of a giant newborn. The market is large, but the system is still in its infancy. Since the Shanghai and Shenzhen exchanges debuted back in 1990, the stock exchange has been a destination mainly for retail investors and is infested with market speculation. The Chinese look at buying shares as betting and suits their love for gambling.

Meanwhile, the real estate market crunch dried up nearly all serious capital from hard-working Chinese savers in recent years. Apart from China’s stock markets having long been plagued by opaque listing rules and loopholed corporate governance, it now faces a shortage of investors.

However, the Chinese stock markets’ capitalisation – combining Hong Kong, Shenzhen, Shanghai and Beijing – is today the world’s second-largest. and in need of a regulatory overhaul. This, however, might send ripples across the global stock markets.

A flawed initiative

China’s One Belt, One Road (OBOR) strategy is a global infrastructure spending spree. “Benefactors” so far have been underdeveloped and middle-income economies in Asia, Africa and Central Europe. The reality is most benefactor countries have something China desperately wants, be it political influence, a rare mineral or cheap energy or whatever else the Chinese economy might need to grow.

Projects are often tied to political pacts through which China’s state-owned enterprises get exclusive bidding rights. Often three times the international standard.

Much of the money was being channelled into countries where the risk of debt default was high. Countries such as Kenya, Pakistan, Ghana, Zambia, Argentine and Sri Lanka.

Because some countries are simply “too big to fail”, about $78.5bn of loans from Chinese institutions were renegotiated or written off between 2020 and the end of March 2023. Additionally, Beijing has extended an unprecedented volume of “rescue loans” to prevent sovereign defaults by big borrowers among about 150 countries that have signed up to the BRI.

Overall, poorly chosen projects funded by cheap loans not only undermine the host countries’ ability to repay debts. But ultimately puts pressure on China’s banking system and its Central Bank – already under strain from the property market crash.

Chinese banks’ asset quality faces risks from non-performing loans, Moody’s analysts said in March 2023. Moodys maintained a “negative” outlook on China’s banking sector. This could lead to a credit crunch in China and significantly slow down the economy. This, as we have learned the hard way, may lead to a slowdown in the global economy.

A changing relationship

The relationship between China and the rest of the world is changing, and a great deal of value could be at stake, depending on whether there is more or less engagement. Businesses and investors alike will need to adjust to the uncertainty ahead.

Trade relationships have evolved between various countries and remain an important part of international diplomacy. Yet, our portfolios feel an impact when these relationships flourish or deteriorate.

We’ve recently witnessed trade tensions escalate between China and the US in the semiconductor industry. Further, the US and Europe announced the implementation of additional export controls on certain advanced computing and semiconductor manufacturing equipment aimed to reduce China’s access to advanced computing technology.

That said, China maintains strong economic partnerships with several countries, including the US, and the global flow of goods and services is an important part of business planning.

While some broad-based global portfolios may not be directly invested in China, there are other things to consider, such as China’s role in manufacturing or supplying the items necessary for global industries to continue operations. So any change in relationships will have an effect on supply chains, and this will ultimately have an impact on investment portfolios.

Investment portfolio impact

A slowdown in exports in 2015 marked China’s slowest annual pace of growth in more than two decades. China’s deceleration was part of an official plan to shift from unsustainable growth from exports and wasteful investment to slower but steadier expansion based on consumer spending.

China’s slowdown and a global oil glut crushed commodities and energy prices. The Standard & Poor’s GSCI commodities index plunged 34 per cent that year to its lowest level since 1999. Down 80 per cent from its peak. And the main culprit was China’s slowdown. While booming, Chinese factories had devoured about half the world’s copper, aluminium, nickel and steel.

The freak-out finally hit global markets in August 2015. Between Aug. 10 and Aug. 25, the Dow Jones industrial average plunged 11 per cent on fears that everyone had underestimated China’s troubles and their impact on the rest of the world.

Today China‘s prominence on the world stage and escalating tensions with major partners threaten supply chains. This, in turn, can have significant implications for investments.

Investment portfolios around the globe can sometimes feel the pain of supply chain disruptions. Ultimately it is trade relationships that play an important part in business continuity and company success. It is a fact that these trade relationships determine share prices and, thus, investment portfolio decisions.

Important considerations like geographic allocation can have a significant impact on investment returns and should be considered in the context of more broad portfolio construction. Investors need to consider direct and indirect exposure to China and other countries for that matter. It is paramount for investors, including those from the Western hemisphere, to understand that focusing only on the more well-known stock exchanges like New York, London, Tokyo, or Singapore will not do the trick. Ultimately we invest in a global world – so we need to think globally and not regional.

Quick Read

Since opening up to foreign trade and investment, China has been among the world’s fastest-growing economies.

The wealth of people in China has grown faster than anywhere else in the world.

China‘s status as an economic powerhouse is indisputable.

China’s economy has slowed sharply in late 2021 and early 2022 to below 5% growth rates.

China faces strong headwinds when it comes to economic growth:

A slowdown in Chinese exports in 2015, hit global markets. Between Aug. 10 and Aug. 25, the Dow Jones industrial average plunged 11 per cent.

Trade relationships determine share prices and, thus, investment portfolio decisions.

It is paramount for investors, including those from the Western hemisphere, that every investment is ultimately an investment in the global world. So we need to think globally and not regional.