My dear Friend,

We all talk about Russia, but do you know how many countries are currently sanctioned?

The US imposed sanctions on six countries and persons from 21 countries.

The EU imposed sanctions on 31 countries. Actually, unlike the US, they only restrict certain goods or forbid financial transactions with a country. This includes governments, provinces, members of governments, specific industries and individuals.

The countries most heavily sanctioned are Russia, Iran, North Korea, Cuba, Syria and Venezuela.

However, economists and the IMF`s recent economic forecast show that sanctions do not seem to do the trick any more.

But who then bears the consequences of such measures, and most importantly, may sanctions impact portfolio performances too?

A tool of diplomacy

First, I would like to point out that it is “a sanction”; therefore, sanctions would be a bundle of punitive measures imposed by one country or a group of countries on another country. They are among the toughest actions nations can take short of going to war.

A sanction or a number thereof is used when a country or regime violates human rights, wages war or endangers international peace and security. The purpose is to change a country‘s undesirable behaviour (Russia, Iraq, Yugoslavia, Syria), limit the opportunities for undesirable behaviour( Iran, North Korea)or deter a country from choosing an undesirable course of action.

A sanction comes in all shapes and sizes and greatly varies in number, country and situation. Possible measures are:

The UN, the US and the European Union hold disproportionate power to impose sanctions, and they frequently do so. Sanctions may seem appealing in principle since, compared to war, they may provide a lower-cost method of punishing departures from international standards of conduct and of resolving disputes between countries.

Brief History

Economic sanctions are not a novel concept in international diplomacy. In fact, economic warfare is as old as warfare itself. However, they would have been called siege or blockade back then. The first recorded use of “sanction” was in 432 BC, when the Athenian Empire banned traders from Megara from its marketplaces, thereby strangling the rival city state’s economy.

Fast forward to the nineteenth century, economic sanctions consisted primarily of sea blockades— blockades that involved the deployment of a naval force by a country or a coalition of countries to interrupt commercial intercourse with specific ports or coasts of a state with which these countries were not at war.

Such blockades were typically initiated by powers that were militarily much stronger than those of the targeted nation and in

the exercise of the right to deploy the blockades.

A means of Peace

The idea of applying pressure to civilian societies and economies was originally seen as part of the repertoire of war. In the wake of a destructive World War I, however, the desire to banish war from the earth forever grew stronger. Therefore the victors created a new international organization, the League of Nations, the pledge to unite the world’s states and to resolve disputes through negotiation. The birth of this modern international institution after the First World War is instrumental in affecting the switch in blockade/sanctions. Actually, this organisation is today called United Nations.

Article 16 of the Covenant of League of Nations declared sanction to be henceforth a means of peace rather than a weapon of wartime. Its founders believed they had equipped the organization with a new and powerful kind of coercive instrument for the modern world-imposing sanctions on “disobedient” nations, thus avoiding war forever.

“A nation that is boycotted is a nation that is in sight of surrender. Apply this economic, peaceful, silent, deadly remedy and there will be no need for force. It does not cost a life outside the nation boycotted, but it brings a pressure upon the nation which, in my judgment, no modern nation could resist..”

Woodrow Wilson, Us President in 1919

The “l´arme économique”, or “the economic weapon, had been tried successfully During World War I. Allied powers, led by Britain and France, had launched an unprecedented economic war against the German, Austro-Hungarian, and Ottoman empires. They erected national blockade ministries and international committees to control and interrupt the flows of goods, energy, food, and information to their enemies.

The alternative to war

Today, economic sanctions are generally considered to be an alternative to war. For most people in the interwar period, however, this new economic weapon was worse than total war. “Sanctionists” regretfully noted the devastating effects of pressure on civilians but nonetheless wholly accepted them.

For example, sanctions imposed on Nazi – Germany and its allies caused a severe impact on Central Europe and the Middle East, where hundreds of thousands died of hunger and disease and civilian society was gravely dislocated. In fact, economic sanctions proved to be a very potent weapon.

“we tried, just as the Germans tried, to make our enemies unwilling that their children should be born; we tried to bring about such a state of destitution that those children, if born at all, should be born dead.”

William Arnold Foster, Administrator of The German Blockade, Author, Human Rights Advocate, labour politician, 1886-1951

The initial intention behind creating the economic weapon was thus not to use it. To interwar internationalists, economic sanctions were a form of deterrence, prefiguring nuclear strategy during the Cold War. Of course, sanctions were not nearly as immediately destructive as nuclear weapons. But for anyone living in the pre-nuclear decades of the early twentieth century, they raised a frightening prospect. A nation put under comprehensive blockade was on the road to social collapse.

The experience of material isolation leaves its mark on society and casts its long-lasting socio-economic and biological shadow over the targeted society for decades afterwards.

Too much of a bad thing

When you look at the crises of the 1920s and ’30s, you find that internationalists struggled not with the weakness of sanctions but with their unbelievable strength. In the aftermath of the blockade during the First World War, they found it difficult to use these instruments of economic pressure, particularly against larger countries, without provoking a war and thereby having the cure be worse than the disease.

Economic sanctions were applied against Soviet rule in Russia and Hungary in the aftermath of the Russian Revolution. A number of liberal and conservative Western leaders argued the increased poverty and starvation in Russia was the cause for the failure of the Russian Revolution spreading elsewhere.

In their view, trying to tame “irrational” revolutionary passions was much better by opening up these economies to the plenty that capitalism brings. Herbert Hoover was one of the major representatives of this position, along with Winston Churchill and David Lloyd George.

Whether during the crisis in Manchuria in 1931 or as fascist Italy invaded Ethiopia in 1935, the League of Nations faced genuine political difficulties and issues of calibration as it tried to use the tool of economic coercion that, in the First World War, had proven itself capable of really serious effects.

The imposition of country-based sanctions can have a massive adverse effect on the economy and humanitarian well-being of the targeted country. Kofi Annan, the former Secretary General to the United Nations, recognised in his 1997 report to the UN that country-based sanctions tend to inflict the most harm on vulnerable civilian groups and can cause great damage to third states.

Uninspiring track record

Wilson’s vision did not work out. More recent history shows that sanctions don’t work reliably and rarely produce desired results. In the runup to World War II, boycotts and bans against Germany by the allied forces and against Italy by the League of Nations didn’t bring about their collapse.

More recently, the vigorously imposed sanctions against Iraq since the 1990s delivered only limited outcomes; over 2,000 accumulated sanctions on North Korea neither impacted its trade with China, its largest trading partner, nor led to de-nuclearization.

Unilateral sanctions—even when imposed by the largest economy in the world—face far more complex challenges, especially in an increasingly integrated international economy. Even against such small and vulnerable targets as Haiti and Panama, military force was eventually required to achieve the goals.

Studies conducted since 1980 found that 35% of the studied 115 cases of economic sanctions were partially successful. The study also concluded that sanctions are the most effective if:

- The goal is relatively modest

- The target country is much smaller than the country imposing sanctions, economically weak, and politically unstable.

- The sanctioner and target are friendly toward one another prior to the imposition of sanctions and conduct substantial trade.

- The sanctions are imposed quickly and decisively to maximize impact.

- The sanctioning country avoids high costs to itself.

Effects Globalization

It is important to know that the study also found that the success rate of sanctions declined since the Second World War. Many factors contribute to these results, but a large part of the explanation must be the effects of globalization.

If a country’s economy is highly integrated globally and has the possibility to circumvent bilateral sanctions, then the sanction will lose its relevance.

Economic sanctions surely provide a policy tool short of military force for punishing or forestalling objectionable actions. However, they have ripple effects well beyond the sanctioning and the sanctioned country’s borders. They can be costly to their targets and third-party economies amid increased global trade and economic interdependence.

One of the causes of this failure may be third-party spoilers, or sanctions busters, who undercut sanctioning efforts by providing their targets with extensive foreign aid or sanctions-busting trade. By analyzing over 60 years of U.S. economic sanctions, Bryan Early reveals that both types of third-party sanctions busters have played a major role in undermining U.S. economic sanctions.

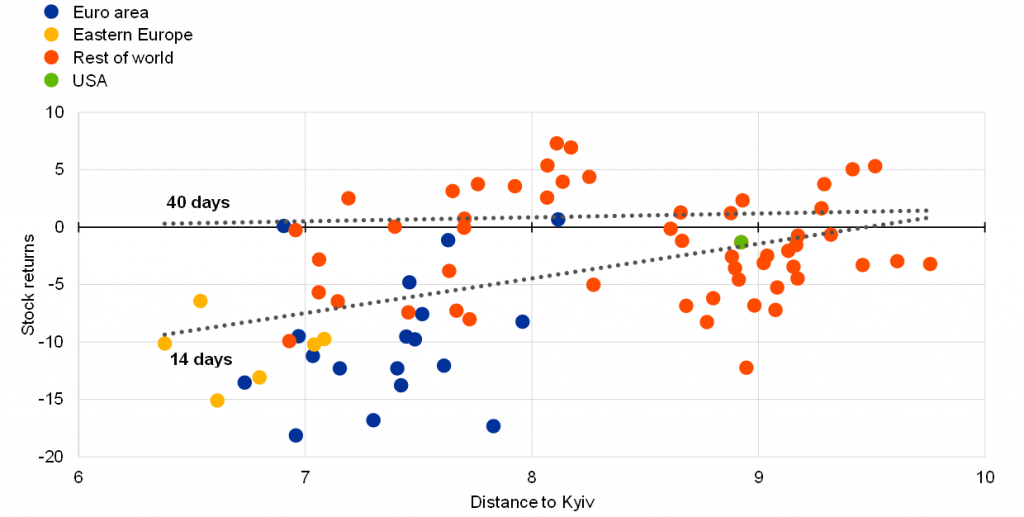

Stock market returns vs distance to Kyiv

Notes: The dots show the percentage change in the respective countries’ stock indices within the 14-day period starting on 25 February versus the distance (in the log) between the capitals of each country and Kyiv. The first regression line suggests that equity markets in countries bordering Ukraine, notably the European markets, have corrected more significantly in the first days after the invasion compared to other equity markets in the rest of the world that are more distant from the invasion. The second regression line is flat, suggesting that the relationship does not hold anymore after 40 days as the geopolitical premium fades due to contamination effects from other shocks.

Collateral damage- the costs

While the benefits of economic sanctions are elusive, the costs often are not. The economic damage done to the ” punished” country often leads to human rights violations such as lack of education, social security, food and shelter.

But trade sanctions also deprive the issuer of the gains made from trade and frequently penalize the country‘s exporting firms. Because they are usually the more sophisticated and productive industries in an economy, the issuing country can face a reduction in GDP.

A study tentatively suggests that even limited sanctions, such as restrictions on foreign aid or narrowly defined export sanctions, can have surprisingly large effects on global trade flows. For example, lower exports by the issuing country by only a few billion can lead to substantial job loss (est. 200.000). Additionally, there would also be substantial long-term effects of sanctions for industries of sophisticated equipment and infrastructure equipment and for exports as a whole.

The costs of failed sanctions policies can be significant for the states that impose them, their targets, and the third-party countries they affect.

The elephant in the room

The effectiveness of new economic sanctions on Russia is rightly facing scrutiny. Several Russian agencies, companies, and individuals close to President Putin have already been facing sanctions since its annexation of Crimea in 2014. The United States, Canada, Australia, Japan, the EU and Great Britain upped the previous by imposing further punitive measures on Moscow immediately following its invasion of Ukraine. Today, Russia is the world’s most sanctioned country.

In terms of effectiveness, it is still early to judge the long-term effect of the sanctions on the Russian economy. So far, the provisional balance sheet appears mixed. Yes, the economy is struggling, but contrary to all predictions, it hasn`t collapsed so far. Some analysts even predict a small growth for the Russian economy.

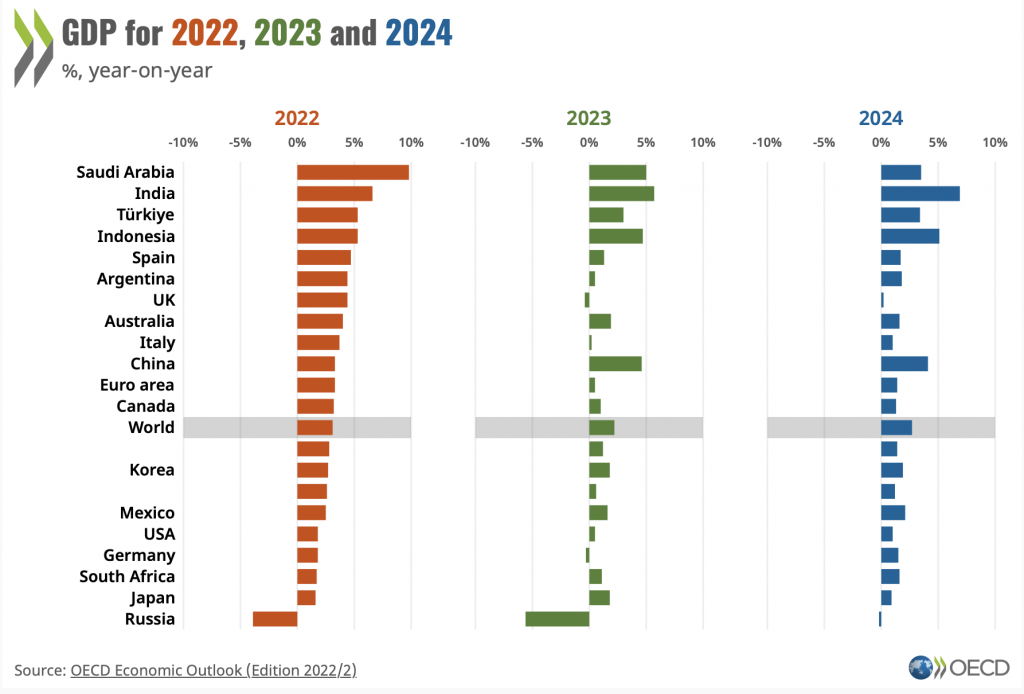

In its October 2022 forecast, the IMF concluded that the Russian GDP contracted by 3.4% in 2022. This, however, is less than the 6% expected in July 2022.

True, half of the country’s foreign exchange reserves have been frozen, and several major banks have been cut off from the international payment system(SWIFT). Yet, Russia‘s central bank swiftly imposed capital controls and raised interest rates sharply, pushing the rouble up steeply.

The Russian government also took extensive measures to keep the unemployment rate low. Due to higher world oil and gas prices, the “Russian oil discount” could be counterbalanced. Additionally, increased sales to China and India partially offset the decline in exports to the EU. The fact is, the country‘s trade balance has improved overall.

On the other hand, EU countries face the highest inflation rates in 40 years. Some of the more industrialized members of the EU will only narrowly escape a recession. Meanwhile, the US‘s inflation rate is not doing much better.

The war has severely affected the international trade system, preventing it from recovering from the shocks caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Olesia Kryvetska, counsel with Asters law firm and head of the Ukrainian Bar Association’s International Trade Law Committee

The economic impact

Punishing Vladimir Putin and Russia for their aggression against Ukraine will cost the global economy and may therefore impact your portfolio as well.

Russia is the world’s 3rd oil producer, the 2nd natural gas producer and among the top 5 producers of steel, nickel, and aluminium. It is also the largest wheat exporter in the world. So this is the reason why the industrialized world is addicted to its exports. Vital commodities are imported from Russia. They are needed for batteries, chips, fertilizers, and baking bread. Neongas, used for consumer electronics and in the car industry, are 5,000% more expensive than before the war.

Economies like Germany, heavily industrialized, may suffer quite a substantial decline in production and exports. This could lead to high unemployment in the long term.

Russia is only the world’s 11th-largest economy. Yet, the all-out sanctioning of Russia has so far resulted in disrupted supply chains, a commodity price surge and high inflation. In effect are sanctioning countries struggling with economic growth while Russia turned around to do business elsewhere – despite discounted prices.

This is the first time a country as big as Russia has been subjected to far-reaching punitive measures in almost a century. The implications were bound to have wide-ranging ripple effects.

“In practical terms, carving Russia out of European banking will be far easier than carving it out of European energy,”

Sam Theodore, Sebnior Consultant, Scope Group

If sustained or exacerbated, higher global commodity prices will likely cause accelerated and prolonged high inflation in many countries, especially in Europe. As a secondary effect, higher commodity prices may also weaken economic growth.

Global Trade

The global trading system has been pushed to its limits since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Trade between the United States and Russia or Ukraine is relatively insignificant compared to the size of either economy. However, suppose the crisis significantly negatively impacts the European economy, there could be a spillover effect on the United States because of the extensive trade between the United States and Europe.

Transport

Another important risk to the global economy comes from how the crisis will affect supply chains for key commodities. So far, several events have raised the possibility of supply chain disruption.

Banks

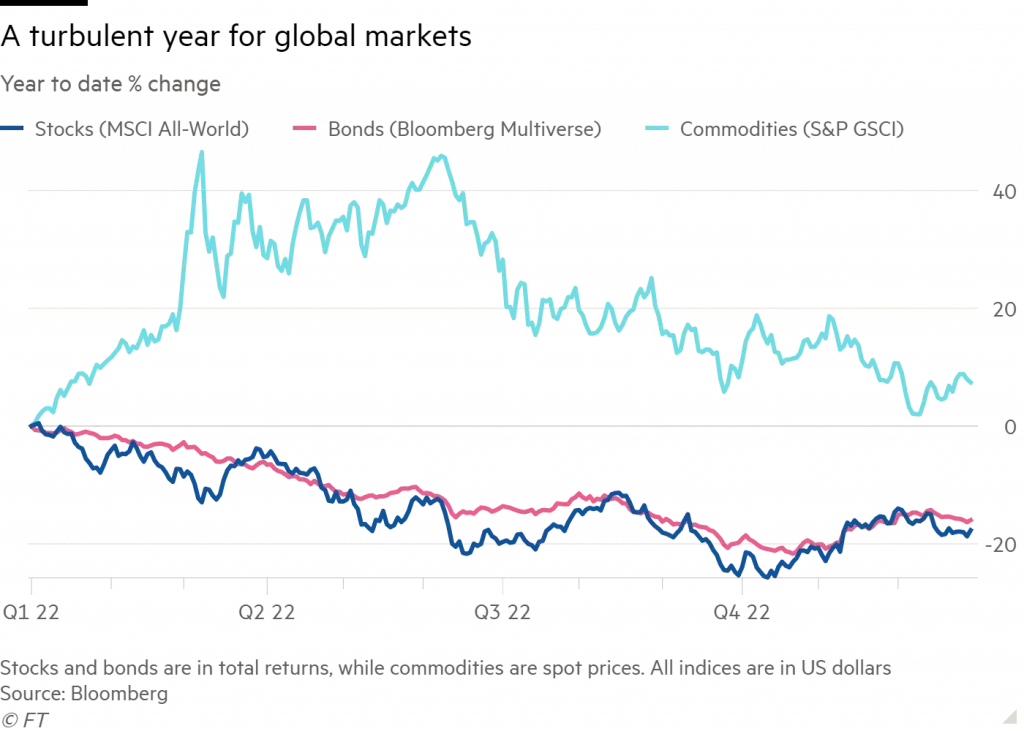

According to Cazenove, 2022 was the worst market year since the Great Depression. Certainly, not all due to the sanctions imposed on Russia, but it would be naive to believe they did not play a role.

Economists almost unanimously agree that the direct impact of the sanctions on the financial markets is likely far less than the secondary effects, such as the increase in the costs of raw materials, energy, inflation, and interest rates.

Europen Banks like UniCredit, Société Générale and Raiffeisen Austria, which had notable links in the Russian market, reassured their investors that the total write-offs would be manageable and would, therefore, not pose a systemic threat.

One problem facing the financial system is a form of multiple-round effects. Eye-watering energy prices and the economic fallout from the war may prevent inflation from coming down. As a consequence, we might see further interest rate hikes. This can bring stock prices down, investments grinding to a halt, and economies end up in a recession after all.

Consequently, the real risk for banks is the worsening of the general economy and the excessive rise in the inflation rate, which could lead to the inability of borrowers to pay their debts.

Insurers

Insurers may be hit on two sides, either through their large investment portfolios or their underwriting. In the latter’s case, they may also be on the hook for indirect losses.

Lloyd’s of London expects the Ukraine conflict to be a major claim in the market this year. That’s despite its underwriting in Russia and Ukraine only representing 1 per cent of its global footprint.

Insurers must also brace for potential impact through exposures across aviation, marine, credit risk and political risk business lines. For example, aeroplane leasing companies now fear they may never get their planes back.

Funds

Fund managers with investments in Russia are stuck with “stranded assets.” Pension funds, hedge funds, and other asset managers have, in many cases, marked Russian assets, ranging from stocks to commercial property, down to zero on their books.

Rating agency Fitch has announced that 10 Russia-focused funds with assets under management (AUM) of €4.2bn have suspended repayments.

Some emerging market funds have Russian exposure for up to about 25% of their AUM and remain trapped in Russian stocks.

However, the European Securities and Markets Authority said for the most part, those closures came down to the difficulties in valuing assets rather than investors’ demands for their cash.

Russian bonds and equities have also been dropped from some investor indices, such as FTSE Russell and MSCI, due to the market being “uninvestable.” Plus, investors could be exposed to any default by the Russian state itself or its major companies.

Clearing Houses

There’s been turmoil in spiralling energy and commodity prices. This spike has a knock-on impact on derivatives markets because banks have to stump up more cash for margin calls if the price moves against their position.

ESMA (European Securities and Markets Authority) described commodity derivatives as “bracing for impact,” including through short positions and margin calls. The London Metal Exchange was also forced to suspend trading in nickel, cancel trades and delay margin payments — due to a short squeeze.

“The invasion has led to significant stress in a range of commodity markets,” a Bank of England report said. “A key uncertainty is whether interconnections within the financial system — for example, between energy and other commodity markets, wider financial markets and the real economy — might create feedback loops and amplification mechanisms across the financial system more broadly.”

Central securities depositories

Central securities depositories play a vital role in ensuring securities trades settle. Meaning one side delivers the bonds or stocks, and the other pays up the cash. So when Russian restrictions kicked in, the two main EU players, Euroclear and Clearstream, were central in cutting off trades in rubles.

As a result of sanctions, central securities depositories are likely to see their balance sheets swell. Fitch Ratings, however, describes the fallout as manageable. Blocked coupon payments and redemptions will most likely accumulate in domestic accounts at Euroclear or Clearstream.

Impact on your portfolio

To some extent, last year’s commodity price increases and the stock market slump reflect fear and risk rather than the effects of actual sanctioning.

Investors likely worried that new events could further disrupt trade in commodities, higher inflation, further interest rate hike and a recession or stagflation.

The truth is most investors have limited exposure to Russia which accounted for a marginal part of global equity and bond indices anyway.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine and the subsequent sanctions, however, will turn some markets into difficult territory for investments. Especially emerging markets could suffer from spillover. Subsequently, shares of companies exporting products to Russia take a downturn as much as emerging market ETFs.

However, the actual knock-on effect on the value of non-Russian assets is more critical to your portfolio. For instance, the lack of ability to export to Russia will dampen developed economies. Subsequently, profits and equity valuations will tumble. As a result, your portfolio may be diminished.

Speed Read

Economic warfare is as old as warfare itself. The idea of applying pressure to civilian societies and economies was originally seen as part of the repertoire of war.

Economic sanctions are generally considered to be an alternative to war.

More recent history shows that sanctions don’t work reliably and rarely produce desired results.

While the benefits of economic sanctions are elusive, the costs often are not. The costs of failed sanctions policies can be significant for the states that impose them, their targets, and the other countries they affect.

Sanctions imposed on Russia since 2014 were upped by the United States, Canada, Australia, Japan, the EU and Great Britain in 2022, immediately following its invasion of Ukraine.

In terms of effectiveness, it is still early to judge the long-term effect of the sanctions on the Russian economy. So far, the provisional balance sheet appears mixed.

So far, the cost for EU countries and the US are substantial. Both have to face the highest inflation rates in 40 years due to rising gas and oil prices and a steep rise in certain commodities. The EU will only narrowly escape a recession.

Punishing Vladimir Putin and Russia for their aggression against Ukraine will cost the global economy and may therefore impact your portfolio too.