Welcome to,

An economic saga leaves investors confused –

the Post-Brexit Economy

My dear Friends,

2022 was an economic nightmare for Great Britain. For 2023 the International Monetary Fund forecasts the slowest growth amongst G7 countries.

Ok, the war in Ukraine has hit most G7 economies – those in Europe were by far hardest hit. And yes, the UK is also wrestling with high inflation, like many other economies.

However, the matter is not that simple, and investors are increasingly confused and put much-needed investments into almost all sectors of the British Economy on halt.

What is really happening, and is the current Post-Brexit Economy confusing?

Economic saga

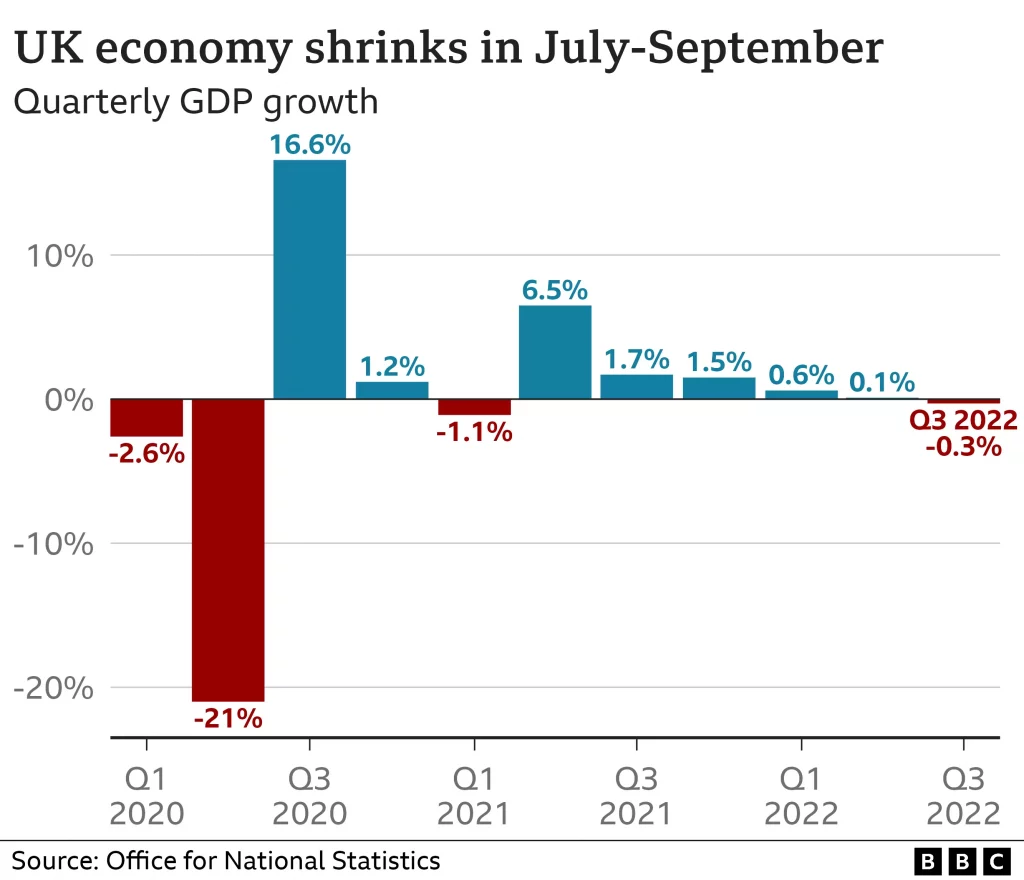

The UK government’s claim that the UK’s Economy is, amongst G7 members, the fastest-growing is misleading. Because the UK experienced the worst decline among the G-7 during the pandemic, its rebound looks bigger, bouncier, and more bodacious in comparison. In fact, the British Economy shrank by 0,3%.

While it is true that global forces play a role, the fact that the UK is forecast to have the slowest growth of any G7 economy in 2023, plus the highest inflation, shows the uniquely bad situation the UK is in.

Inflation

In 2022, UK inflation was at its highest in 41 years, 11,1%(October 2022). The 2023 forecast is not much better, as it will have the highest inflation rate in the G7. Higher than all EU members and will only be exceeded in the G20 by crisis-ridden Argentina, Turkey and Russia.

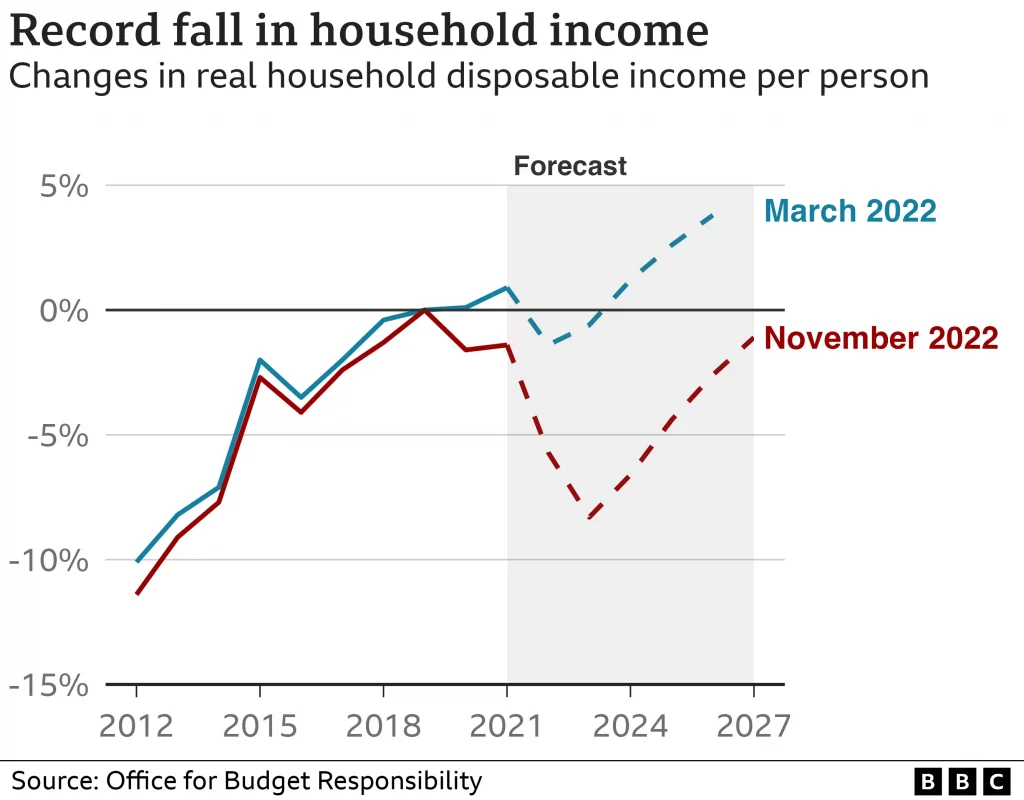

This created a cost of living crisis hitting families across the country. When accounting for rising prices, household incomes continued to fall, and household spending “fell for the first time since the final Covid-19 lockdown in the spring of 2021”.

When adjusted for inflation, household incomes are expected to fall back to the levels they were in 2013. It will take six years to recover, although they will still be “over 1% below pre-pandemic levels” by 2028.

Recession

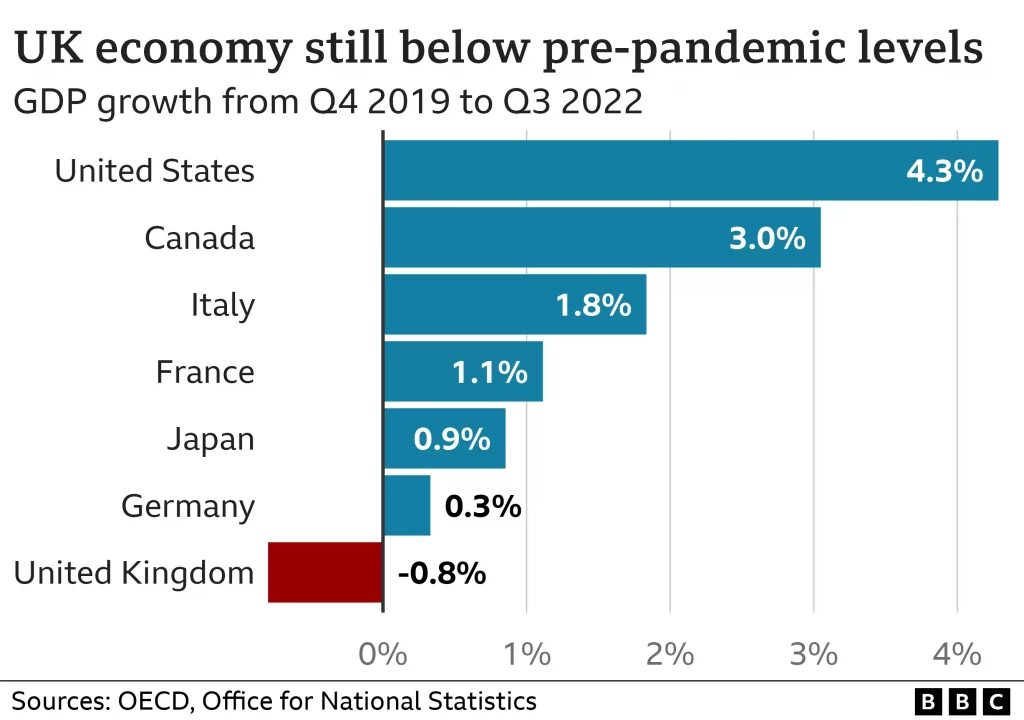

The UK’s Economy is in marked contrast to the eurozone(up 2.2%) or Canada (up 3%). Overall, the British Economy remains 0.8% smaller than its pre-pandemic level.

Because, by definition, a country is considered to be in recession when its Economy shrinks for two three-month periods or quarters in a row. So the British Economy shows clear signs that a recession is looming.

Consequently, companies make less money, pay falls, and unemployment rises. This, in return, leaves the government with less money in tax to use on public services.

The disparity between the UK and the rest of the world looks starker than previously thought.

The forecast

In its 2023 macro outlook, Goldman Sachs forecasts a 1.2% contraction in U.K. real GDP over this year, well below all other G-10 (Group of Ten) major economies.

The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development(OECD) has also forecast that the U.K. will lag significantly behind other developed nations in the coming years despite facing the same macroeconomic headwinds, putting London closer in performance to Moskow than to the rest of the G-7.

The U.K. independent Office for Budget Responsibility projects that the country faces its record sharpest fall in living standards. Real household disposable income, a measure of living standards, is forecast to fall by 4.3% in 2022-23.

KPMG expects the central bank to increase the bank rate to 4% during the first quarter of 2023.

The U.K. faces a unique domestic obstacle – a massive labour shortage. The country‘s parliamentary committee called it the “greatest workforce crisis in their history. One of the reasons is a record number of workers reporting long-term sickness. The other reason, however, is homemade and due to Brexit. The country struggles to bring in fruit pickers, hotel maids and truck drivers. The National Health Service in England is short of tens of thousands of doctors, nurses and midwives.

The country will experience more heavily depleted trade as a result of Brexit. The Economy faces a difficult period ahead, with global headwinds adding to domestic pressures.

High energy prices, elevated inflation, rising interest rates and global economic weakness mean the UK economy is expected to be in recession until the middle of 2023, according to the new ERNST & YOUNG ITEM Club Autumn 22 Forecast.

“Times have changed. London has become a far-off city, bulwarked by marketed conservatives. The incentive for entering this vampiric bastion is not very great.”

André Gordts, Art Collector, now based in Bruxelles

Cirque du Soleil

The U.K.’s already embattled Economy had to face little political stability in 2022. It was a tumultuous year in the United Kingdom, where the only constant seemed to be changed.

In one four-month stretch, the U.K. had four chancellors of the exchequer (essentially Britain’s treasury secretary) and three prime ministers. With one government bringing the Economy, its currency and its credit rating to near collapse with a “disruptive” budget.

Liz Truss‘ and Kwasi Kwarteng‘s controversial fiscal policy announcements on Sep. 23 contained large swathes of debt-funded tax cuts as part of the new government’s aim to drive economic growth to 2.5%.

The new government in power quickly reversed much of the previous government’s budget plans. The markets calmed down but how much this will do to stabilize the Economy or soothe investors‘ concerns is questionable. As there is one question looming, ” what comes next”.

The year concluded with a near 11% inflation and a series of walkouts by nurses, immigration officers, driving test examiners, postal staff and railway workers in the worst strike the country has seen in more than a decade.

“That is a very good example of what happens when you don’t have checks and balances in your constitutional system. Until that’s fixed, I don’t really think anything much is going to improve in British politics.”

Patrick Dunleavy, Professor of Politics, London School of Economics

Muddied waters

England’s Finance Minister announced his “Mini Budget” on September 23rd. The ambitious plans were for tax cuts, largely unfunded which would have resulted in large fiscal deficits, increased government debt and rising inflation.

This created a panic in the financial market. The budget was the opposite of what investors could expect in an inflationary environment. As a result, the British pound fell to an all-time low and a sellout of government bonds.

Moves of this magnitude are highly unusual in the developed world sovereign bond markets.

The British Bond market was increasingly growing dysfunctional. So, the Bank of England intervened and, on September 28th, started an emergency bond-buying program. More or less a total reversal of their previous attempts to fight inflation by raising interest rates.

“The purpose of these purchases will be to restore orderly market conditions. The purchases will be carried out on whatever scale is necessary to effect this outcome,”

Andrew Bailey, Governor Bank of England

On October 11th, the Bank of England announced it would stop its emergency bond-buying by Friday 14th. Only to send the Pound and the bond markets tumbling again, almost causing a spillover into other markets.

To soothe investors’ fears, the Bank of England suggested that it would continue to buy so-called gilts beyond the Friday deadline. But, whatever the assurances, the Bank of England’s credibility was now questioned.

Apart from all the technocratic language, the Bank of England‘s surprise announcement was part of a growing power struggle between the central bank and the government over handling the U.K.’s struggling Economy.

Any loss of confidence in the central bank removes yet another sliver of hope for British investors, who have already been bewildered by Liz Truss‘ government’s choice of economic problem-solving.

“It’s undeniable now that we’re seeing a much bigger slowdown [in trade] in the UK compared to the rest of the world,” she said. We’re definitely underperforming compared to our peers.”

Swati Dhingra , Professor for Economics, London School of Economics

Brexit Economy

Despite claims by the conservative government, the actual elephant in the room is Brexit.

The 2016 referendum was supposed to resolve Britain’s long, tortured relationship with the European Union.

For the first time since leaving the European Union in 2020 — public opinion has turned against Brexit. According to a British Chambers of Commerce survey, more than three-quarters of British firms said the U.K.’s post-Brexit trade deal with Europe is not helping them increase sales.

Another survey found that 56% of respondents believed it was wrong to leave the European Union, with only 32% supporting Brexit.

Rising Costs

The costs of new Brexit trade rules are mounting for British companies that depend on fast, small deliveries from Europe. They now have to contend with additional forms, customs charges and health safety checks for goods to cross Britain’s border.

Some British businesses are taking on the export costs of their European suppliers to avoid losing them. Others are just importing less, reducing the choices for customers. Still, others restrict purchases to bulk orders and forgo trying new products.

“There are higher costs for things like raw materials and a strained supply chain, to which the UK is more exposed to because of Brexit,”

Suren Thiru, Head of the British Chamber of Commerce

Trade

By October 2021, despite Boris Johnson‘s reassurances, UK‘s export had shrunk by 16%. The pandemic aside, the export numbers had shown a similar double-digit export fall prior to Covid-19.

Economists say Brexit has pushed food prices up 6 per cent. Some even claim a 100% rise for specific food items. Retail prices of a broad range of goods also surged, including clothing, food, used cars, alcohol and tobacco, as well as books, games and toys.

The additional paperwork and import tax add 30-35% to export/import costs leading to 50% less profit for UK businesses. Many, especially small businesses, decide to stop exporting/importing to the EU, leading to an acute shortage of goods, leading to higher prices and ultimately resulting in even higher inflation.

Britain is staring down the spectre of stagflation, a ruinous mix of stagnant economic growth and rapid inflation. The country is experiencing the fastest pace in consumer price growth in four decades — an 11% per cent inflation rate(November 2022). Some even predict that Britain’s nightmare economy of the 1970s may be making a comeback

Labour shortage

Rising prices inflict pain worldwide, but Britain faces more persistent problems than many of its neighbours. The country has a tight labour market. This is partly because of Brexit, which took away a sizeable European labour pool, and because long-term sickness has kept hundreds of thousands out of work.

The UK labour force has declined by 473,000 since the pandemic’s start. On top, the exodus of EU citizens from the UK workforce is significant. Net EU migration fell from nearly 300,00 in 2016 to zero by 2021. It should, however, be pointed out that the shortage is most significant in the low-wage and service sectors. The hospitality, health, shipping and farming sector are the worst hit. More than half of the companies in that sector suffer from a labour shortage.

So while many individuals struggle with the cost of living crisis, employers look like they’re suffering a “cost of leaving crisis” from Brexit. It might subsequently come as less of a surprise to learn that (according to Office for National Statistics data), almost a third of businesses are experiencing a shortage of workers.

As labour shortages emerge, wage-setting power shifts back to workers. This increased bargaining power means that there is a chance that wages will be higher over the long run, too. In other words, competition for workers could also mean higher wages, inflation, and interest rates. However, this could leave the UK facing higher inflation and a permanently lower potential growth rate.

Big Bang 2.0

The UK has one of the largest financial systems in the world. The City of London generated 10% of the UK‘s economic power. Since Brexit, however, UK imports of financial services from the EU have declined, and hundreds of banking and finance organizations have left the UK and relocated to the EU.

Since the UK’s EU referendum, 44% (97 out of 222) of the largest UK financial services firms announced plans to move some UK operations and staff to the EU. This figure nearly doubled between March 2017 (53 out of 222, 24%) and March 2021 (95 out of 222, 43%)

The government is doing all it can to make the UK, and the City in particular, look more competitive to international businesses. One key area of focus is remodelling the UK’s financial regulatory framework. The government is planning to repeal EU rules in favour of giving domestic regulators the powers to regulate the sector.

In 2021, the then chancellor, Rishi Sunak, set out a vision for the sector and what it hails as a “Big Bang 2.0” for the City of London post-Brexit. The UK government plans ambitious reforms so that the financial services industry can lead both domestically and internationally. However, little to nothing has been implemented so far.

The proposals essentially involve the shedding of EU regulation in favour of a home-grown regulatory framework.

This leaves some very concerned that such an overhaul may move towards a more light-touch form of regulation, making the City of London even more attractive for dirty money than it had already been. This could prove to be a questionable business model.

Global Britain

Brexit supporters previously touted the prospect of a US-UK trade deal as a critical benefit of leaving the EU.

Since it left the EU, the UK has had the freedom to pursue its independent trade deals.

The UK has signed trade deals and agreements in principle with 71 countries and one with the EU.

The truth, however, is most of these “new” deals are simply “rollovers”, meaning they copied the terms of deals the UK previously had when it was an EU member rather than creating new trading arrangements.

The US, a desired and significant trading partner– 16.6% of total UK trade,- has so far not signed any major trade deal with the UK. Some small agreements have been reached – such as lifting the ban on the export of British beef. However, the promised and desired treaty has not happened and is unlikely to do so in the near future.

“The UK chose Brexit in a referendum, but the government then chose a particularly hard form of Brexit, which maximized the economic cost, any hope for economic upside from Brexit is pretty much gone”

Michael Saunders, Senior adviser at Oxford Economics, former Bank of England

Confused

The UK has regained its sovereignty at a very high price. The Office for Budget Responsibility states that Brexit will lower the UK‘s GDP by 4% for the next 15 years.

Brexit has cracked Britain’s economic foundation to the core and has damaged business investment, which in the third quarter of 2022 was 8% below pre-pandemic levels.

The pound has taken a beating, making imports more expensive and feeding inflation while failing to boost exports.

Brexit has erected trade barriers for UK businesses and foreign companies that used Britain as a European base. It weighs on imports and exports, sapping investment and contributing to labour shortages. All this has exacerbated Britain’s inflation problem, hurting workers and the business community.

According to the Confederation of British Industry, a leading business group, the fall in private sector activity picked up in December and has declined for five consecutive quarters.

The downward trend “looks set to deepen” in 2023, principal economist at the Confederation of British Industry, Martin Sartorius, said in a statement.

The confusion will persist, as there is no handbook for such a drastic change in economic policy. Nor can anybody forecast what effect another negative development of the global economy will have on the UK economy. Nothing like Brexit has ever been done before, and nobody really knows how to deal with it.

Quick Read

The UK is forecast to have the slowest growth of any G7 economy next year, plus the highest inflation.

2022 was a tumultuous year in the United Kingdom, where the only constant was change.

The English Finance Minister‘s “Mini Budget” created a panic in the financial market.

Due to Brexit and the pandemic UK‘s export has shrunk by 16%(October 2021).

A shrinking workforce could mean higher wages, inflation, and interest rates. This leaves the UK with higher inflation and a permanently lower potential growth rate.

The City of London generates 10% of the UK‘s economic power. Since Brexit, UK imports of financial services from the EU have declined. The Tory government’s plans to revive the financial services industry are controversial.

The UK has signed trade deals and agreements with 71 countries and one with the EU. Most of these “new” deals are simply “rollovers”.

The Brexit confusion will persist, as there is no handbook for such a drastic change in economic policy.