Brexit Briefing:

Facts, Spin, and Gaslighting 101

Making Sense of Brexit

My dear Friends,

Brexit formally began when the UK left the EU on 31 January 2020, while continuing to follow EU rules through the rest of the year. After thousands of hours of talks, Michel Barnier(EU) and David Frost (GB) had been negotiating for 11 months. In the meantime, the British public was exposed to serious gaslighting—both sides announced a deal on Christmas Eve 2020. Extra transition months were built in to give the UK and EU breathing room to negotiate the post-Brexit relationship.

The agreement was ratified by British Parlament on December 30th, 2020, the European Parliament ratified the agreement on April 27th, 2021. The agreement entered force on January 1st 2021, to avoid major disruption.

Needless to say – like in any post divorce negotiation- to find comon ground for the post brexit deal took further negotiating and negotiating and negotiating ……

Let’s rewind to pre-referendum Britain, and separate memory from myth. Coming up : Britains brief encounter with the EU and the Brexit referendum playbook—gaslighting included, of course.

Down the Rabbit Hole

1961 the UK applied for membership in the EEC (later EU), and the Conservative politician Harold Mcmillan was Prime Minister. In France, Michel Debré was Prime Minister, and Charles de Gaulle was President.

1961 the UK was struggling with a national shortage of money, an adverse balance of payments, the imposing of a wage freeze, and other deflationary measures. The Nassau agreement (December 1962) between Macmillan and Kennedy enraged Charles de Gaulle, who then was head of the French state and who insisted on a Europe uncontrolled by the United States. So France vetoed the UK´s membership in the EEC.

1963 and 1967, the UK, first Sir Alec Douglas-Hume, and from 1965 Sir Edward Heath, as Conservative Prime Minister, applies again for EEC membership. In France, Georges Pompidou was Prime Minister, and Charles de Gaulle was still President, vetoed again.

Despite having been victorious in WW2, the UK was not keeping up with the economic growth pace of other European countries. Britain’s finances were fragile; rising inflation, high unemployment, and crippling labour strikes brought the country to a near standstill. UK´s share of global manufacturing had gone down to 4,9% due to trade unionism and lack of innovation.

De Gaulle distrusted the British not only because of their close relationship with the US but also because of the differences between the French and British farming industries. France´s agriculture accounted for 25% of the country´s GDP, a dilapidated and highly unprofitable industry with 2 million farms. The EEC´s (EU) Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), a highly subsidized single market for agricultural goods at guaranteed prices, was de Gaulle’s only way to maintain France’s and economic and social stability. Subsidizing sales, buying surplus stock, and imposing levies on importing cheaper goods outside the EEC was major tool to stabilize France. As a result of emergency wartime measures, Britain had an efficient farming industry, and only 4% of the UK´s GDP could be assigned to the agricultural industry. France fears that with the UK joining the EEC (EU), CAP would be off the table and France´s economy and social stability threatened.

… a number of aspects of Britain´s economy, from working practices to agriculture make Britain incompatible with Europe

Charles de gaulle, 1962

1969, Charles de Gaulle´s Presidency had come to an end, and George Pompidou was the new President; green light was finally given by all members of the EU to start negotiations with Great Britain. 1973 the UK becomes a full member of the EU.

Ever since, the UK membership can be considered as continuously turbulent, mainly due to the UK’s inherent opposition to surrendering national sovereignty, and the EU is more than a kind of “club for doing business”.

1975, two years after becoming a member, a first national referendum on whether the UK should remain in der EU is held. Harold Wilson, the Labour Prime minister, contested the October election of 1974 with a commitment to renegotiate Britain’s terms of membership with the EU. 67.2% were in favour of staying in the EEC.

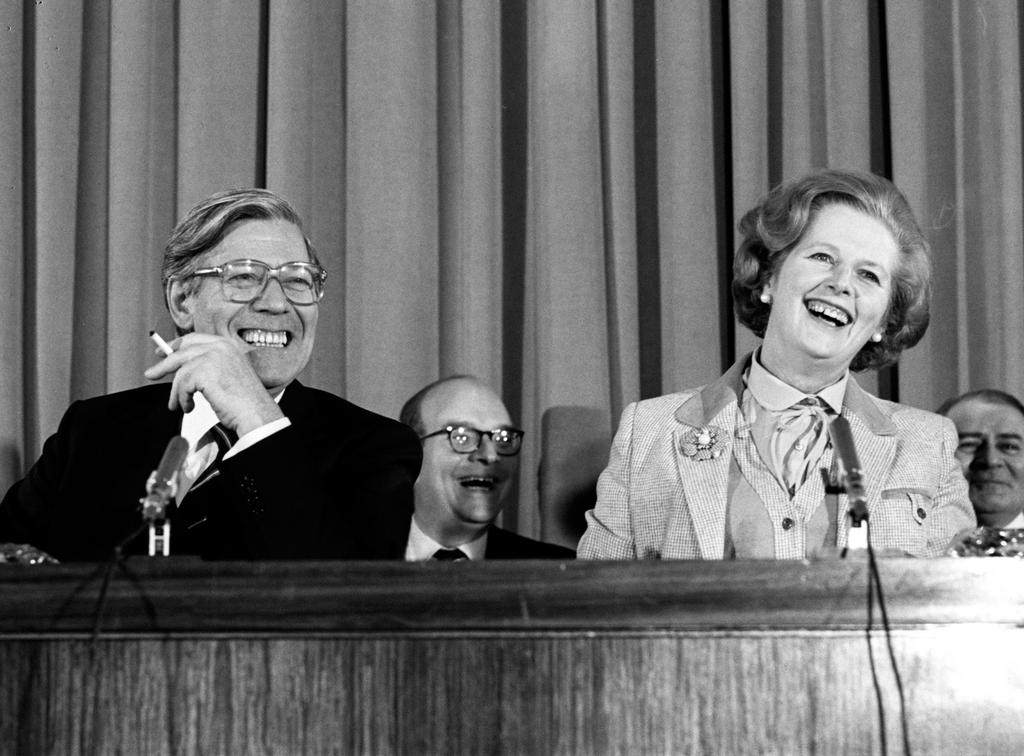

1979-1990, the conservative prime minister Margaret Thatcher negotiates a special rebate for the UK. She strictly opposes more political integration and a “European Superstate”. The Treaty of Rome was revised, and the Single European Act was signed. The UK joined the European Exchange Rate Mechanism(ERM), and the Pound was now pegged to eight other European currencies with a fixed exchange rate.

At home, the Conservative government pushes major privatization and deregulation. Competition policy became the rule with the consequence of deindustrialization and a rise in structural unemployment. The Financial Services Act of 1986 led to massive deregulation in the financial markets, dubbed as Big-Bang.

1986-1989 the UK was an economic boom era; by 1989, however, inflation had risen to 10%, and recession was looming.

1990-1993 the UK economy faces a recession seen as the worst since the Great Depression(1929). As a result, three million people were unemployed. 1992, the pound sterling came under pressure, due to restrictions by the ERM and because of currency speculations. The Bank of England tried to stabilize the currency. By September 1992, the UK was forced to withdraw from the ERM. The pound was severely devalued, and the cost for the treasury amounted to GBP 3 -27 Billion, depending on the source. The bill was footed by the British taxpayer -the Conservative party lost all credibility for economic competence.

Worth Noting

In the months leading up to Black Wednesday, among many other currency traders, George Soros had been building a huge short position in pounds sterling that would become immensely profitable if the pound fell below the lower band of the ERM. Soros believed the rate at which the United Kingdom was brought into the Exchange Rate Mechanism was too high, inflation was too high (triple the German rate), and British interest rates were hurting their asset prices.

Eurosceptic views were on the rise amongst Conservative Party members. In 1993 the UK Independence Party (UKIP) was formed, soon after Sir James Goldsmith formed the Referendum Party (1994). In 1993 Eurosceptics accounted for 38% of the population; by 2015, the number had risen to 65%.

2004 the EU grows by eight Eastern-European countries. Fifteen member states agreed to implement a seven-year transition period; during this period, members of the new EU member states could not take up jobs in any of the “old” member states. Only Irland, Sweden, and the UK decided to waive the transition period. The record number of people coming to live in the UK(Non-UK Nationals) was around 400.000. In 2014, 853.000 Polish Nationals lived in the UK.

The now booming economy was running up against skills shortages, so Tony Blair, Labour Prime minister (1997-2004), waivered the seven-year transition period for the new member state´s workforce but also abolished the primary purpose rule for Non – EU immigration. From late 2000 until 2008, the UK opened its doors to mass immigration.

The 21st century sees the completion of the UK economy´s transition from manufacturing, which had been declining since the 1960s, to considerable economic growth with services and the finance sector. In contrast, the public sector continued to expand.

On 23 June 2016, UK’s second EU referendum took place. Again it was a politician who promised to hold a referendum should he win the 2015 elections, David Cameron, a Conservative Party politician.

The UK had just renegotiated their membership in the EU. After 10 weeks of campaigning, the people of Great Britain voted 52% against 48% leaving the EU, and David Cameron resigned as Prime Minister. The turmoil begins…

The Brexit vote upended Britain’s politics, divided its people, and fundamentally altered its business environment.

Some of the fallout was immediate. The day after the referendum, the value of the British pound plummeted to its lowest point in history, triggering a period of rising inflation. After the vote, business investment stalled. Companies were too unsure about Britain’s major trading relationships to make big decisions.

Essentials

2020 UK´s GDP dropped by 9,9%, and the Confederation of British Industries (CBI) forecasts GDP growth of 8,1% for 2021- KPMG states a 4,6% rise in GDP

UK´s rise in GDP will entirely depend on the British consumer´s behaviour. A rising unemployment rate and a resurgence of insolvencies would crash these forecasts

Public debt will rise to 110% of GDP by 2023- as a result, the cooperate tax rate will most likely go up

The UK`s agricultural and food industry slowed down by 59% and will continue to slow down

Brexit related murky waters regarding the service sector will dampen the recovery

Low interest rates, reduced currency risks, and heavily subsidized infrastructure programs could drive an uptick in selected commercial real estate investments

What has the European Union ever done for Brits?

Before Brexit, the soundtrack was simple: “Brussels costs, Britain pays, nothing gained.” Classic gaslighting—repeat a distortion until it feels like fact. In reality, membership delivered everyday dividends. This isn’t nostalgia; it’s an audit — and what was quietly written off in the noise.

- The freedom to live, work or retire in 28 European countries

- The freedom to set up a business in 28 European countries

- The UK science received £730 million a year in EU funding for research

- 2015, 3.1 million British jobs were linked to the UK’s exports to the EU

- British farmers receive considerable EU subsidies, helping to bolster agriculture and ensure job stability in the sector

- The EU accounts for 44% of all UK exports of goods and services

- The success of the UK financial market services is largely due to EU Internal Market legislation

- Free movement of labour has helped address shortages of unskilled workers (fruit picking, catering)

- The EU accounts for 47% of the UK’s stock of inward Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), worth over $1.2 trillion

- Structural funding for areas of the UK hit by an industrial decline (South Wales, Yorkshire)

- The benefits of cross-country coordination and cooperation in the fight against crime.

- The CBI estimates that the net benefit of EU membership is worth 4-5% of GDP to the UK, or £62bn-£78bn per year.

- A peaceful Northern Ireland

The Truth

The UK’s net contribution to the EU budget was around 0.4% of GDP (less than an eighth of the UK’s defence spending)

Since 1985 the UK has received a budget rebate equivalent to 66% of its net contribution to the EU budget

The UK has to pay GBP 32.9 Billion to the EU as a settlement

Brexiting: The Never-Ending Farewell Tour

Resignations, resets, and reheated red lines—Britain negotiated mostly with itself. Europe waited; Westminster whirled. New negotiator, same binders. From envoys to Prime Ministers, the revolving door did more work than the deal.

June 2016: David Cameron resigns

July 2016: Theresa May becomes Prime minister

March 2017: The UK triggers Article 50. This means negotiations on the UK leaving the EU can begin. The EU and the UK have two years to reach an agreement.

June 2017: May calls a general election and loses her majority in parliament

December 2017: The Backstop as a solution for the Northern Ireland issue is conceived. The EU27 (EU member states except for the UK) establish that sufficient progress has been made in phase 1. Phase 2 of the negotiations can begin. They start discussing a transition period and explore their future relationship.

March 2018: The EU and the UK reach a provisional agreement. It includes a transition period until 31 December 2020, in which all EU rules continue to apply. It also covers the border between Ireland and Northern Ireland.

July 2018: The Brexit Secretary Davis Davies resigns, and Boris Johnson takes his place

November 2018: The Withdrawal Agreement draft does not contain the Backsackstop. The European Union and the United Kingdom reached a draft withdrawal agreement. The UK government and the 27 remaining EU member states approve the draft agreement.

January 2019-March 2019: Theresa May, the Prime Minister, failed three times to get the agreement through parliament. The main worry is the UK will have to remain in the customs union due to the Backstop. First, May lost by 432 votes to 202. Two months later, she lost the vote again, despite reassurances by the EU the Backstop would be only a temporary solution. The third time around, she lost by a margin of 58 votes.

April 2019: Due to May´s failure to get the deal through parliament, the deadline is declared “flexible” until October 2019

May 2019: Theresa May gives up and declares to stand down by June 7th. The UK participates in EU Parliament elections.

July 2019: The Johnson era begins “deliver Brexit, unite the country and defeat Jeremy Corbyn.”

August 2018: Johnson suspends parliament; in September, the Supreme Court declares this action unlawful

September 2019: Members of Parliament are back, and Johnson demands a general election and brands prorogation ‘unlawful, void and of no effect. The “Benn bill” becomes law, preventing the UK from leaving the EU without a deal.

October 2019: The UK sends a new Brexit Plan to Brussels, and the Backstop is removed- the European Commission rejects the proposal. Leo Varadkar, the Irish Priministerrim, and Boris Johnson meet to find a “Nothern Ireland Solution”. The UK and the EU suddenly declare a deal had been struck – British MPs withhold their approval. Boris Johnson is forced to ask for another delay. A ” flex tension” is granted by the EU until the 31st of January 2020

December 2019: Ursula von der Leyen is the new European Commission President and Charles Michel the new European Council President. Boris Johnson wins the election with ease. In Northern Ireland and Scotland, the anti – Brexit mood has gained momentum.

January 2020: The Withdrawal bill makes it through the UK parliament, and the European Parliament approves the “divorce deal” as well.

Brexit is far from over. Yet, Brexiteers are keen on closing down any debate and on declaring victory by staunchly defying reality. In the process, they use populist rhetorical devices, which may very well damage the British democracy further by undermining any basic norms of reasonable and honest argumentation.

CHRIS GREY ´WE ARE STILL BREXITING´

March 2020: Future relationship talks begin and are quickly interrupted due to Covid-19

April 2020: Talks resume virtually in an attempt to get negotiations back on track

June 2020: Mr Johnson urged the EU to “put a tiger in the tank”, while the EU’s Charles Michel refused to buy a “pig in a poke”.

September 2020: The UK plans new legislation that would override key parts of the Brexit withdrawal agreement relating to the Northern Ireland protocol. The EU said the attempt to override the Brexit treaty was not only an infringement of international law but one that threatened the Northern Ireland peace process.

October 2020: Mr Johnson suspends the future relationship negotiations, saying that the EU was not serious about the talks. Mr Johnson said talks could continue only if there were a “fundamental” rethink on the EU side.

November 2020: Several deadlines pass

December 2020: A deal is struck- a 1.246-page document is released. Brigid Fowler, a senior researcher at the Hansard Society, describes the process as a “farce” and “an abdication of parliament’s constitutional responsibilities to deliver proper scrutiny of the executive and of the law”.

“a failure for both sides, but better than nothing”.

Guy Verhofstadt, EU PARLIAMENT Brexit Co-ordinator

Gaslighting

Gaslighting: repeat a distortion until doubt feels like clarity. In the Brexit years, claims of costless freedom and effortless trade were sold as common sense while evidence was brushed aside. Below, a few greatest hits—what was promised, and what reality delivered.

The UK-EU trade deal prioritises sovereignty over market access. Politicians will soon be talking about how to improve the deal. Very little about the UK’s long-term relationship with the EU has been settled.

The government-sponsored Centre for European Reform

“There might be closer cooperation, but I doubt it at the moment. What’s more concerning is the government’s gaslighting. They don’t admit that there’s a problem; they play it down; they say to wait 10 years. Which one is it? Is it all fine or do we need to wait 10 years? And what are the people currently suffering supposed to do in that time?”

Anand Menon, professor of European politics at King’s College London.

“It’s entirely possible that 10 years from now, the UK will have pivoted to exporting beyond Europe. My concern is that it will be as part of an overall reduction in trade, meaning a smaller economy and, ultimately, job losses.”

Simon Usherwood, professor of politics at the University of Surrey.

“It makes my blood boil. I think they are in denial because they cannot handle the consequences of their policies. They are battering some of our greatest industries and trying to distract everyone by picking fake fights and starting culture wars.”

Alastair Campbell, former Prime Minister Tony Blair’s director of communication

“The British public will never eat enough fish to make up for lost European business. For every man at sea, another 20 jobs rely on them onshore. Boris Johnson spouts on about investing millions in fishing over the next five years. In five years, he might have destroyed the whole industry.”

Andy Trust, fisherman from Cornwall

The Crystal Ball and Britain’s Economy – Post Applause

The government is planning a “super deduction” tax break to bolster investment. That could spur spending, but the underlying pace of growth is unlikely to return to its pre-referendum level.

It’s too soon to unpick the overall impact on trade, especially for more than 180,000 British businesses whose only experience of international trade was with the E.U. New customs checks, veterinary requirements, and other regulations have already restricted the movement of goods. New agreements with far-flung countries aren’t expected to replace the deal Britain had with its nearest neighbours as a member of the E.U. By the government’s own estimates, its new trade deal with Australia will increase G.D.P. by as much as 500 million pounds (about $700 million) over 15 years, or 0.02 per cent of output.

A glimmer of hope

The U.K. and India want to double trade between their two countries by 2030, up from over $15.4 billion in 2019-2020; unlike many of India’s other trade talks, which have lingered for years without an outcome, there is a strong chance of a deal with the U.K. given the needs of both the sides. The price will most likely be increased immigration of labour from India to the UK.

The financial services industry, one of Britain’s most prosperous sectors, resigned early to diminished status in Europe. This year, European shares and derivatives trading has shifted out of London, and banks are still moving employees to other European capitals. In response, the British government is trying to revive London’s reputation as a finance hub by overhauling rules on listings — welcoming SPACs, among other things — and loosening regulations for start-ups.

Industries that relied heavily on European workers warned from the start about a looming labour crisis as it became harder for E.U. citizens to move to Britain. As the country recovers from the pandemic, that crisis has arrived. Restaurants and hotels have been hampered by staff shortages. There are warnings that there aren’t enough food production workers or truck drivers.

Recovering from Covid won’t be easy for any country. Still, businesses in Britain are not only on the trail of the worst recession in three centuries but also contending with the end of a four-decade economic union. It could be another five years or more before we know the true shape of Britain’s post-Brexit economy.

A thought to take with you:

Today, you know more than you did yesterday. Imagine where you’ll be next week.

– yours, Harper